Growing up, I remember when my mother would play her favourite record of Japanese traditional folk music and she would sing along. One of her favourite songs was Sakura, Sakura, celebrating the beauty of cherry blossoms in full bloom. Even now when I see sakura, there is an automatic response to sing the opening lines to the song aloud or quietly in my mind when people are around.

I never realized what an impact sakura (cherry blossoms) would have on my life.

Currently spending time in Victoria, B.C., I am fascinated by cherry and plum trees blossoming all over the city. Victoria boasts one of the mildest climates in Canada, so it’s usually the first city to start blooming, often months before the rest of the country. The blossoms remind me of hanami, the centuries-old practice in Japan of picnicking under a blooming sakura or ume (plum) tree. It is one of the things I loved most about being in Japan.

Sakura and Hanami

In Japan, the blossoms were spectacular during hanami but what touched me most was the deep appreciation, respect and wonder the Japanese have for the blossoms. While the cherry blossoms in Canada may signify the arrival of spring, in Japan they have deeper meaning. The cherry blossoms come once a year for a short time and for the Japanese, represent life itself. There is beauty in life, which is fleeting, so we need to appreciate it fully while we have it.

With the approach of warmer weather front, the Japanese Meteorological Agency tracks the sakura zensen, the progress of flowering cherry blossom trees and provides daily forecasts on news programs. The Japanese pay close attention to these forecasts and turn out in large numbers at parks, shrines and temples with family and friends to hold flower-viewing picnics with special food and drink.

Why are there so many cherry trees in Victoria?

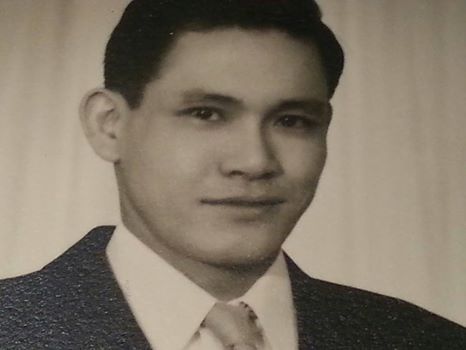

I wondered why there are so many Japanese cherry trees in Victoria. It was intriguing that Canadians of Japanese ancestry were uprooted from their homes and relocated to camps in the interior during the Second World War, including my grandfather Ishii and his family, while the Japanese cherry trees in Victoria, Vancouver and along the B.C. coast, remained rooted and became more endearing to communities.

In the 1930s, Victoria City Parks superintendent Herb Warren began a campaign to replace the overgrown roadside native trees whose roots were heaving sidewalks and blocking sewage drains. Japanese flowering cherry trees were the right size, upright and ornamental. Warren envisioned canopies of blossoms to attract visitors and new residents.

However, the Depression-era parks committee could allocate only so much toward tree stock and labour. Instead the campaign’s boost came from Victoria’s Japanese community.

In 1937, Victoria held parades to celebrate the 75th anniversary of its incorporation. A float sponsored by Victoria’s Japanese Community Association was admired and praised, and won a cash prize of $300. The association donated the prize money to the city for the purchase of 1,013 Japanese flowering cherry trees for Beacon Hill Park and the city’s boulevards.

Since that time, people with ties to Japan have donated cherry trees as gifts in Victoria, Vancouver, and along the B.C. coast. In the 1930s, the mayors of Japanese cities, Kobe and Yokohama, presented Vancouver’s park board with 500 Japanese cherry trees for planting at the Japanese Canadian War Memorial in Stanley Park to honour Japanese Canadians who served in the First World War. In 1958, Japanese consul Muneo Tanabe followed up with another 300 cherry trees as “an eternal memory of good friendship between our two nations.”

In 1959, Shotaru Shimizu, former owner of a 30-room New Dominion hotel in Prince Rupert, B.C., arranged for 500 Japanese cherry blossom trees to be imported and planted in the city. His generosity is remarkable because it occurred after the forced wartime relocation in 1942, of himself and his family, along with confiscation of their property and goods, and the postwar ban on returning to the coast to live.

Today, Vancouver is famous for its thousands of blossoming trees during springtime. More than 40,000 cherry trees line the streets and live in the many parks of the city. In Victoria, the beautiful pink and white blossoms are a trademark part of the city, attracting tourists and bringing locals pride and joy.

Ann-Lee Switzer co-author of the 2012 book, Gateway to Promise: Canada’s First Japanese Community, explains the significance of the cherry blossoms,

“For residents and visitors alike in Victoria, spring only comes alive when the sakura appear. The plum blossoms come out earlier, but the days still hold a chill in the air. But towards the end of March when the cherry blossoms begin to burst out, everyone can feel true spring in the warm air. The sakura represents a renewal of the cycle of the year as no other event. If the sakura did not bloom each spring in the city, a void would be felt by all.”

How peaceful cherry blossoms created a heated debate in Victoria

In late February 2019, the Victoria Nikkei Cultural Society (VNCS) president Tsugio Kurushima was asked to comment to media about the City of Victoria replacing its flowering cherry trees with native tree species. The rationale from the parks department was that native trees are better suited to the effects of climate change than the imported cherry trees.

The VNCS mounted a campaign to lobby against any uprooting of cherry trees, including issuing a news release and recruiting a tree biologist expert, Dr. Patrick von Aderkas, from the Centre for Forest Biology, University of Victoria. Dr. von Aderkas contradicted the city’s position that cherry trees are more susceptible to climate change. He stated that cherry trees have excellent adaptation capabilities regarding climate change better than most native species.

In media interviews, the VNCS president expressed his opposition and sadness at the proposal to remove the cherry trees because of the historic connection of the trees and the Japanese Canadian community and that they are an iconic feature of Victoria that would be missed by everyone.

Kurushima explained the significance of the blossoming trees, “It was a gesture from the immigrant community to thank Victoria and Canada for allowing us to start a new life in Canada.” He added, “it’s disappointing that City Hall has failed to consult with Victoria’s Japanese community and the wider community about council’s plans that could uproot history.”

Shortly after the VNCS news release went out, the VNCS got a call from Victoria’s Mayor Lisa Helps who stated it was never the intent of the city to replace the cherry trees. She said that one of the councillors misunderstood their tree management plan and gave out wrong information in an interview which led to this misunderstanding.

Victoria’s city council passed a motion on Feb 28, 2019. It recognizes the historic importance and symbolic significance of cherry blossom trees, encourages that cherry trees be maintained as part of the city’s tree management program, and that the mayor would write to the Victoria Nikkei Cultural Society to express appreciation for their historic gift and clarify the city’s policy regarding the cherry trees. Because of the proactive and diligent work of the VNCS, the cherry trees will remain a feature of Victoria for the foreseeable future. Although this issue has dissipated, the VNCS says it will remain vigilant.

What sakura mean to me

Sakura in B.C. are a reminder of the Japanese communities that once thrived here but were uprooted due to war and prejudice. They represent the spirit of the Japanese Canadians who were interned.

Despite being exiled from their homes into camps and stripped of their possessions, they persevered. They understood that life and beauty are precarious like cherry blossoms so we must appreciate what we have and go on despite difficult circumstances. Despite cramped shacks and harsh weather conditions, they stood upright and remained proud. They faced hatred and prejudice before, during and after the Second World War and didn’t break.

After the war, they flowered against all odds, not being able to go back to their homes and businesses after the camps, having their possessions sold, and being left with almost nothing.

With future generations, including myself, there is renewal and forgiveness. We must remember the struggles of our ancestors and bring this compassion to strangers who are different from us and we may not understand. By doing this, we plant seeds for true understanding and new growth.

Centuries later, the words of Kobayashi Issa, Japanese haiku poet and Buddhist priest, are relevant today more than ever,

In the cherry blossom’s shade, there’s no such thing as a stranger.

0 Comments