OCHI, Japan — It’s been over six months since I arrived in Ochi, a small rural town in Japan. Before I came to Japan, I asked my friend in Ottawa, whether she preferred Canadian or Japanese winters. She answered right away, “Canada.” Surprised, I asked, isn’t it colder here? She replied, “yes, but not inside.” I was confused.

Only living through a winter in the rural Japanese countryside, do I understand what she meant. It’s warmer than in Canada, rarely dipping below 0 degrees Celsius and warming up to 10 degrees Celsius on sunny days. However, it often feels cold inside.

At the junior high school where I am an assistant English teacher with the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program, I often say I’m cold. It’s the remark I frequently hear from teachers and students, binding us together like talking about how bad the weather is back home.

I took central heating for granted in Canada. Here, the schools are not well heated. In my home, there is an overhead air conditioner/heater in one room. I spend most of my life there. It’s set up like a dorm room, where I sleep, eat and watch movies, though I have a spacious sparsely furnished two-bedroom apartment. Being cold inside is something that has taken me a long time to get used to, and I’m not sure I will ever get used to it.

Have I fallen out of love with my town? Speaking with a good friend one night, I was complaining about what I didn’t like about being here. She said don’t blame poor Ochi. I knew she was right and felt awful for blaming the town.

It took me a while to understand that the problem rests with me. We all have a narrative playing in our heads. The voices that have been in mine for so long were of being a victim and helpless. Why couldn’t I have gotten a posting to an urban area as I had asked? Why can’t I be like my JET colleagues who seem to enjoy being on their own and in the countryside?

I noticed that the narrative I had in my head was defeating me at every turn. Observing this, I realized how much negative and critical self-talk there is. We are quick to blame everyone and everything!

When I changed the words in my head to more uplifting ones, such as presence, love and fun, my life changed. I felt more positive, and so did the world around me.

We possess the remote controls to our lives, but we forget. I didn’t know how to do this at first because I never learned how to love and take care of myself. I knew how to criticize, neglect, and not take care of myself. This was easy. Not enough sleep, eating in a rush, toxic relationships and being hard on myself.

I used to push Caroline so hard that she would suffer and want to quit. I realize now that the reason I allowed others to speak to me critically because I believed what they said to be true.

I didn’t know Ochi existed before I came here. I didn’t want to go to the rural countryside. I was afraid it would be dark, cold and isolating, and there wouldn’t be much open at night. This has all come true, it is the reality of living in the countryside.

There is so much to complain about in our lives. Gratitude has been the antidote to being unhappy with things in my life that I can’t control. With gratitude, my heart opens, and the light comes in.

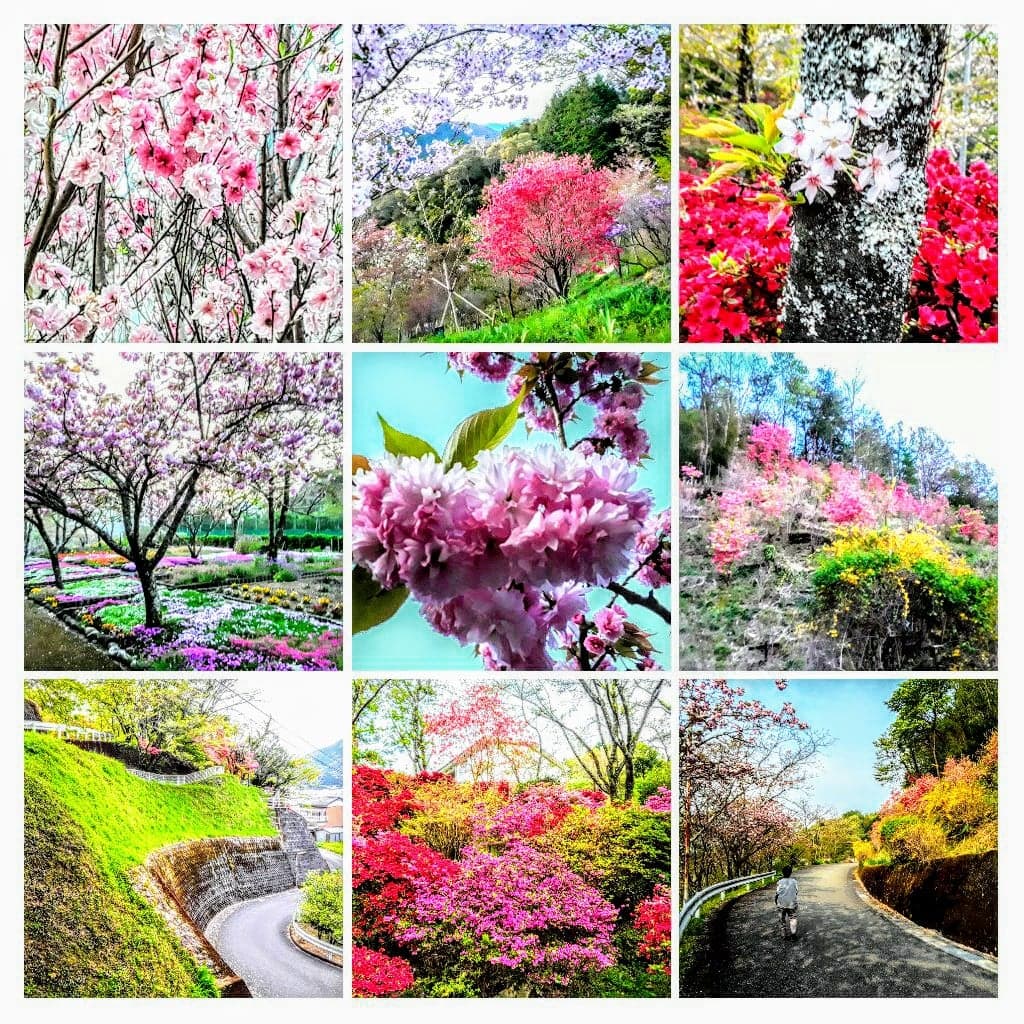

Every day as I walk in Ochi, I am grateful for the beauty around me. The plum blossoms coming out despite the cold, the tiny flowers hidden among the cracks in the worn pathways, and the green moss on the stone walls.

It snowed one day in Ochi, a rare occurrence, and blanketed the town in a beautiful veil of white. I loved hearing the students laughing and squealing in joy as they played in the snow, whether having snowballs fights or making snowmen before the snow melted. I could feel magic and joy in the air. There is beauty everywhere when we look for it.

I resisted loving Ochi, but I have fallen back in love with it. I will not be here forever, but while I am, I want to live a life of no regrets, being present and grateful for where I am now versus looking toward the future and other people to make me content with my life.

We may not be as comfortable as we’d like to be, but can we still be happy anyway?

I’ve written the top things I love about living in Ochi. This is a valuable exercise for the places and people that matter to us, but we have become disgruntled with over time. Our hearts remember, but our minds may need a reminder.

What do I love about Ochi?

Food. The fresh seasonal produce is exceptional, plentiful and inexpensive, coming directly from the mountains and fields where they are raised with care. One of my favourite dishes is inakazushi (mountain vegetable sushi). Made with fresh mountain vegetables, it’s beautiful, delicious and healthy.

Japanese language. Living and working in Japan, I am amazed at how much Japanese is coming back from my childhood. My mother spoke to me in Japanese when I was a child, and I replied in English. I went to a Japanese language school on Saturdays in Toronto, which I resented because other children my age were watching Saturday morning cartoons. With each day, I understand more and can express myself better.

Nature. Steep mountain ranges covered with ancient green forests, yellow-brown brush from the rice fields, resting until the next growing season. Plum blossoms are starting to appear now, and in the fall, there are vast fields of cosmos flowers, Ochi’s flower, and a big festival to celebrate them. The Niyodo blue river, named because it is mysteriously blue in some places, winds through the town and is one of the cleanest rivers in Japan.

People. The Ochi residents are genuine, cheerful and generous.

They share produce from their gardens, bring beautiful homemade desserts to share with school staff, and help me navigate through the Japanese language and customs. They say hello when I pass them in the street. When students see me in town, they call out my name and wave, surprised to see me out of my habitat of the school.

Students. The junior high school students are noisy and unruly at times like they are back in Canada. However, they are also charming and often make me laugh with their honesty, innocence and enthusiasm. Most don’t have cell phones and communicate in person or by landline phone. They write a lot by hand, whether their homework, assignments or tests.

Community. Ochi values collaboration and cooperation and taking care of each other. The students often work in teams in the class. In one class, students were asked to work on their own, and one student said to the teacher, “it’s kind of lonely working alone, don’t you think?” Ochi also has many community activities, from festivals to sports events, and everyone is encouraged to participate, from the young to the old.

Even in a mountain area where the school closed long ago, the Ochi Board of Education holds an annual sports event at the school with the community, made up of mostly local elderly women. The board shuttles in students from our junior high school, along with town officials and staff.

Towns like Ochi hold the secret for Japan’s longevity. This can be attributed in part to the traditional Japanese diet, which is healthy and mostly plant-based and served in small portions. Students eat a hot Japanese lunch every day at school, cooked by the on-site kitchen and served by assigned members of each class.

Japan’s most significant contributor to longevity and happiness lies in the community. There’s a strong connection between generations, close-knit friendships, and a sense of belonging. Lives having meaning and purpose and individuals know that the community values them.

Ochi is like many rural towns in Japan, with a declining population, and a large elderly population. Many students will go off to the cities for high schools, universities and jobs, and few will return home to live. What will happen to Ochi?

I have learned so much from being in Ochi, much from the unexpected and unplanned. I once asked the prolific travel writer and poet Pico Iyer what he would say to his younger self. He told me, “nothing ever goes as planned.” He wished he had learned this earlier in life. I am still learning.

I ended up not where I had hoped to be. But it is where I needed to come. The most significant constraints in our lives are the ones that we create for ourselves. I am grateful to be on this journey of the unexpected and unplanned life. I’m still cold in Ochi, but I’m happy.

Photography: the collage has some favourite taste memories, starting from left to right: kinkan bite-size citrus fruit and fresh ginger (Kochi is the largest producer in Japan); making fresh konnyaku (jelly made from devil’s tongue potatoes) with primary school students; gobo (burdock root); watermelon daikon radish and other vegetables; spring tempura; kaki (persimmon); inakazushi (countryside sushi) with mountain vegetables; sakuramochi (sweet rice cake with a red bean filling, wrapped with a pickled cherry blossom leaf and topped with a salted sakura), only available during the sakura season, and yomogi daifukumochi (mugwort rice cake with red bean filling) and sakuramochi, because you can never have enough mochi!

0 Comments