I finally found my grandfather, Otomatsu Ishii, after 70 years.

Otomatsu Ishii, 29, left Japan aboard a merchant ship in 1902. In return for three years of hard labour building the Penticton Railway in B.C., my grandfather received his Canadian citizenship and made his way to Kingcome Inlet, northeast of Vancouver Island, to do what he loved, fishing.

In 1917, Asa Kajikawa, 28, came to Canada from Hiroshima as a picture bride. She was a widow with two young sons. She wanted to provide for her children and thought that she could send money back from Canada and see them again. This would not be the case.

My grandparents’ first home was a floating house along Kingcome Inlet, where they had two daughters (Hisako and Harue) and two sons (Yoshinobu and my father, George). In 1929, Otomatsu bought half of North Rendezvous Island, north of Vancouver Island, about 160 acres. The family worked hard to clear and cultivate the land. Two more children, Asao and Toshiko, were born on the island.

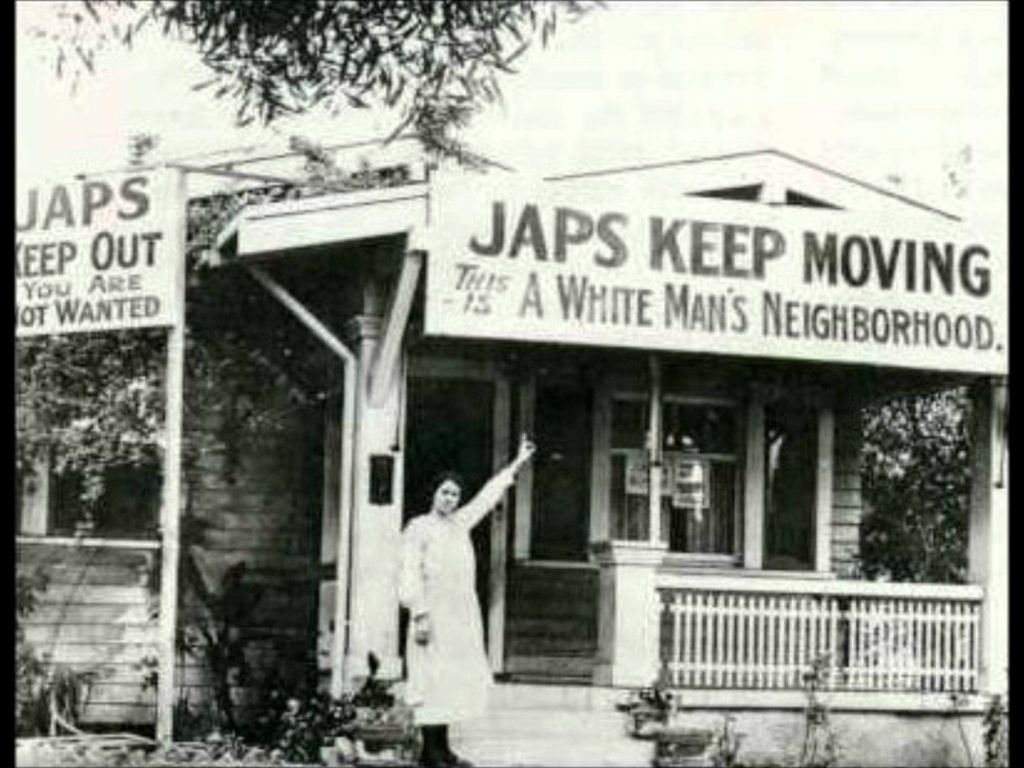

When Grandmother Asa came to Canada, she didn’t know that Second World War change their lives forever. My grandparents and their children were sent to internment camps, despite being Canadian citizens whose children were born in Canada. Forty years of Otomatsu’s life in Canada were reduced to one suitcase for each family member.

At the end of the war, my grandparents were given a choice, either move east of the Rockies or to Japan. In 1948, Otomatsu brought his family to his hometown, Nushima, Japan. My uncle Yoshinobu and aunt Hisako and her new husband moved to Ontario.

In Nushima, Otomatsu hoped that he would find the family home. But the war had ravaged Japan, including his hometown. His brother had died and there was nothing left of the family home. At 75 years old, he had nothing in Canada or Japan and couldn’t provide for his children. He was heartbroken and told his children to find their way back to Canada. Grandmother Asa searched desperately for her family who lived near Hiroshima but could not find any trace of them. She presumed that they had died when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. She was devastated.

After the family arrived in Nushima, George and Harue left to find work in Osaka. My grandparents stayed in Nushima with Toshiko and Asao, so they could finish school. Otomatsu died of cancer on July 15, 1949. His last request was for his ashes to be placed in the Ishii gravesite in Nushima.

At the end of that year, George, Asao and Toshiko returned to Canada, sponsored by Hisako and her husband. Harue followed and Grandmother Asa finally rejoined her family in Toronto in 1962 and died in 1966.

Nushima is one of the smallest of the inhabited islands in Japan, 10 km in circumference and with a population of 400. Rich in spiritual history and located off the southeast coast of Awajishima Island, people have lived there since 400 BC and fishing has always been part of their lives. Nushima is one of the legendary Onokorojima Island places appearing in the famous Kuniumi story (Japan’s creation mythology). The story says that the gods Izanagi and Izanami churned up the sea with a spear and when a drop of seawater fell back to the sea it solidified to become Nushima Island. The couple created a towering 30-metre pillar on the coast called Kami Tategami Iwa (God Rock) and were married on top of the rock. They gave birth to Awajishima Island as the first island of Japan.

This August, I arrived in Ochi, Japan, to work as an assistant English teacher with JET, the Japan Exchange and Teaching Program. The beautiful nature, rugged green mountains and rice fields and clear water took my breath away.

I told many people I met in Ochi the story of my family history and my desire to visit my grandfather’s gravesite. When I told my friend, Rika Kataoka, a generous, caring and enthusiastic person, she said, ‘let’s go to Nushima!’

Rika asked me about my grandfather and Nushima to locate my Otomatsu’s gravesite. I contacted my aunt Tomo in Toronto, who is our family’s unofficial historian. She provided more details and photos to help us with our search. Rika spoke with the Minamiawaji City Hall to ask how she could find a gravesite in Nushima. Rika was surprised when she received a call from the Nushima branch office. They told her they found Otomatsu’s gravestone, in Renkoji Temple.

On Dec. 7, 2019, I went to Nushima with Rika and my good friend and fellow JET Lee Yeonkyung as support. It was a three-hour drive to the Nada Dongho Harbor in the southern part Awajishimi Island, where we took the 10-minute boat ride to Nushima.

Seeing the outline of Nushima island in the distance, I felt like I was in a dream. We were picked up at the ferry terminal by the owner of the guesthouse where we were staying called Asayama.

After a delicious local fish dinner prepared by the guesthouse, the owner said she would call some of the older people on the island. She thought someone might have been around at the same time as the Ishii’s and remember them. She called a few people with no luck.

The next morning we went to the Renkoji Temple. Rika had made an appointment with monk Takimoto-san. We walked up the stairs and narrow alleyways to the temple, on top of a hill with large trees, manicured shrubs and stone pathways. Takimoto-san came out to the steps of the temple to greet us. The inside of the temple was even more beautiful with intricate gold artwork, delicate woodwork, large windows and is filled with sunlight.

Takimoto-san brought out the official book of death records. Each entry was written in beautiful shodo (Japanese calligraphy). He pointed out what he thought was the record of my grandfather’s death in the book. He showed me the entry, Rika read the kanji to me, “Otomatsu Ishii who died on July 15, 1949.” It felt surreal to find something you’ve been searching so long for.

Takimoto-san and his wife invited some older women from the town to join us for tea in case they could remember the Ishii family. We discussed their lives in Nushima and they shared photos, but they did not remember the Ishii family.

As we were chatting, Takimoto-san’s wife noticed an elderly woman leaving the graveyard beside the temple. She invited her to join us and we asked her about my family. She said she remembered an Asao Ishii from Canada. I said, “that’s my uncle!” We all breathed a big sigh of relief and smiled, mine the largest because the connection had been found.

We had the official record of my grandfather’s death at Renkoji Temple. But to have someone who was in contact with my family when they were here, in a way, felt like it proved my existence.

Takimoto-san said he said he thought he found the Ishii gravesite but wasn’t sure because it hadn’t been taken care of in 70 years. He brought us to it and cleaned up the kanji with his fingers. I could read the kanji for Ishii and Rika read the rest. He lifted the gravestone and explained that families used to hide the ashes of their loved ones inside the gravestone monuments. He glanced inside but couldn’t see anything. I looked at the stone and touched it.

In seeing my grandfather’s gravestone and putting my fingers on it, I felt that I was touching something profound inside of me that I hadn’t been touched before. It was the pain, sadness and guilt that my grandfather carried with him when he died. It is now known through the study of epigenetics that ancestral pain and suffering can be transferred from one generation to the next through altered genes from traumatic events.

We had heard about the famous Kami Tategami Iwa rock and wanted to see it. At the top of a long hill, with steep cliffs, the raging ocean and rugged shoreline and we saw the giant rock jutting from the sea and knew that was it.

Ishii means stone or rock in Japanese. I call the famous rock an Ishii of love. In fact, it is an island of love. The gods Izanagi and Izanami fell in love and created Nushima. My grandfather was born here, wanted to return after the war and asked to be buried here because he loved this island. I return here because of my love for my grandfather.

In the end, we cannot erase the pain and suffering we and generations before us and after us will experience. However, we can pass on the love in our hearts for the places and people that we care about deeply.

I found Otomatsu, and in doing so, I found myself.

One night in Nushima, I was walking on the rocks by the shoreline, watching the brilliant red-orange sunset. I spoke in a silent soliloquy to grandfather Otomatsu. I told him why I had come, how things had changed in how people view the Japanese in Canada, and I thanked him for all that he did. The winds blew sharply suddenly, and I thought I heard my grandfather whisper to me, “I know Caroline, thank you for coming.”

Afterward: Recently, the elderly woman we met in Nushima, sent us a letter and a faded photo she found. The picture was of a group of handsome young boys in Nushima and there was Asao!

0 Comments