What is it like to have two identities, one that is visible to the outer world and one that is not?

That’s what it’s like to be Japanese and Canadian. On the outside, people see my Asian features but on the inside, I was born Canadian, as were my parents, and have lived here most of my life.

People often ask me where I come from.

When I respond “Canada” they are perplexed and ask “but where do you really come from?” I say, “Toronto”. It’s a game I play because I know what they want me to say and I don’t want to say it. Though, I will easily tire of playing and say, “I’m of Japanese ancestry.” And they will say, “I knew it, Asian!”.

I was thrilled when I was invited to be a panelist in the recent National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) Conference in Ottawa, Canada that explored what it is to be “Japanese and Canadian”. Being a panelist provided me with the opportunity to reflect on this question which I have been grappling all my life and gather new insight from a sold-out crowd.

I am deeply grateful to the NAJC that is committed to “human rights for all, for the enrichment of Canada.”

In 1941, 22,000 Canadians of Japanese ancestry, including my father and his family, were labeled as “enemy aliens” and incarcerated in camps, deported or sent east to work on sugar beet farms. They were dispossessed of what they could not carry and everything else they owned were held “in trust” but sold in 1942 without permission. The NAJC negotiated a redress agreement and apology from the Canadian government on behalf of all the Japanese Canadians who suffered racism, injustices, discrimination, and dispossession during the war-time period, which was signed on September 22, 1988.

The question the moderator for the panel on the “present” asked, “What has drawn you to Japanese-influenced cuisine and how has this had an impact on your identity and life?”

Here’s my answer.

I was drawn to Japanese food as a child. Actually, I was forced into it. My mom fed me tiny morsels of Japanese food with ohashi (chopsticks). Learning how to pick up my food, however awkwardly, with my own ohashi, was one of my rites of passage.

It would often take the whole day for my mom to cook a Japanese meal for us. After putting my hands in prayer, saying “itadakemasu” (from Buddhism roots meaning to humbly receive), and bowing slightly, I would devour her creations at warp speed.

Looking back, I feel sorry for my mom because she took so much time and care to prepare our meals. But later I realized that in making the food she loved, she nourished herself as well. Because this food brought her “home” to growing up in Japan.

When someone asks me, what would be my last meal I often say “rice”.

I believe you need to be Japanese to understand our deep attachment to rice and the comfort it provides at the deepest cellular and ancestral levels.

Growing up, most of our meals revolved around rice.

My job was washing the rice. I disliked this task because being an impatient kid, it seemed to take forever for the water from the rice to become clear and my hands would get cold and wrinkly in the process.

Rice would start the day with my mom’s favourite traditional Japanese breakfast of hot rice, pickles and miso soup. She would make this only for herself as I would often make fun of her saying, “rice for breakfast!” “Why can’t you be like all the other mothers!”

I was mean but I also know that growing up can be hard on children because they want to fit in with their peers and not stand out.

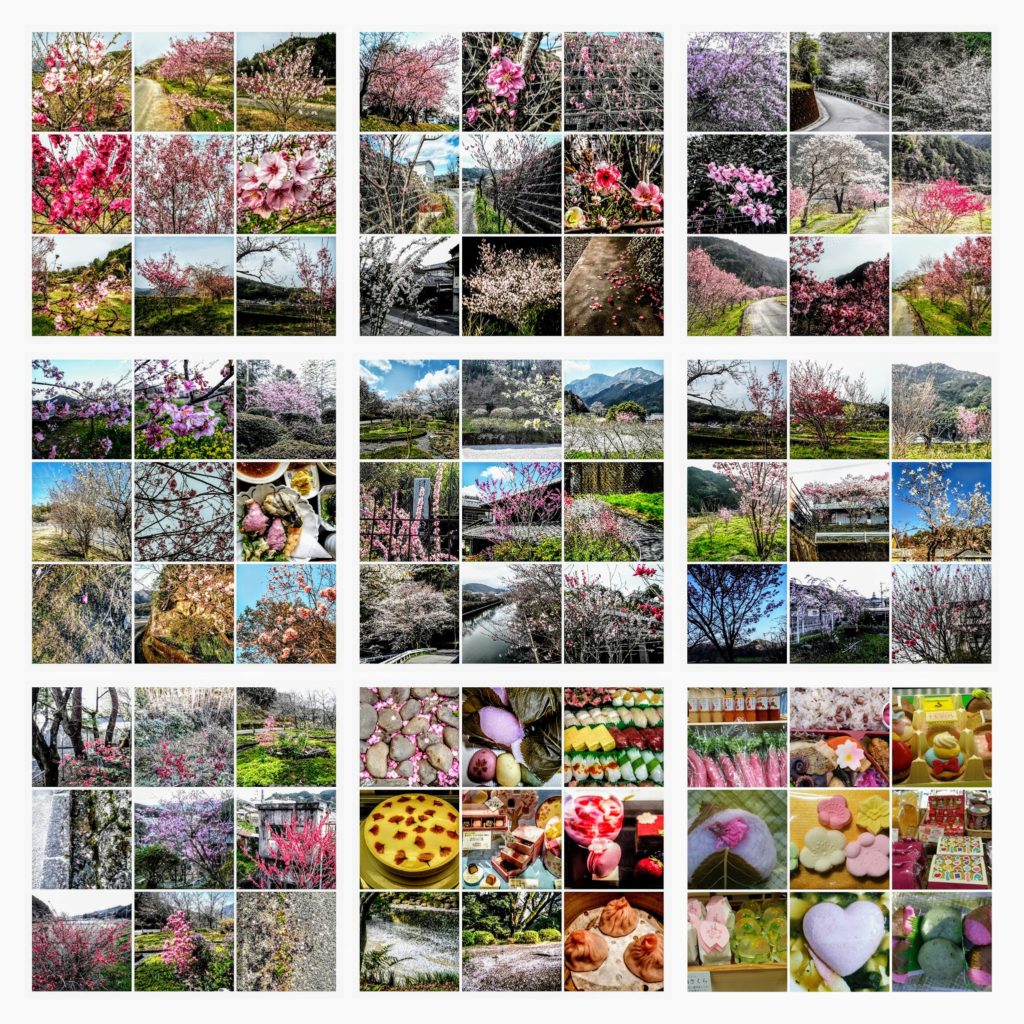

When my mom took me to Japan when I was a child, it was my training ground to becoming an adult, and later a chef, with a deep understanding and appreciation for Japanese culture and cuisine.

In our travels, I would follow my mom to early morning markets with food that would confront and awaken all my senses and often make me nauseous from the strong smells.

We would eat her favourite food, and there were many, from bento boxes on the Shinkansen train and fresh sashimi at a geisha house with her salaryman cousin, to Nagasaki Champon noodles made in her best friend’s kitchen, and takoyaki (batter cooked in a special ball-shaped mould and typically filled with minced octopus) at a street festival.

My mom was excited and happy eating Japanese food. Over time, I became excited for the same foods as my mom, and I love the traditional Japanese breakfast now.

I realize now that my mom passed down to me the taste, texture, and presentation of Japanese food. But more important, the excitement of doing something you love, which for her was eating, making and sharing Japanese food.

I saw that a taste memory once lost from a childhood in Japan could be recovered in Canada, which I call a “taste memory” in my book The Accidental Chef.

Most of all, I was surprised how excited she was to share food with her friends, often long lost from her childhood, and me.

As the chef-owner of ZenKitchen restaurant, I wanted to play with global tastes and have some Japanese home cooking that was close to my heart. Though, I would cringe every time someone would ask me what type of cuisine I cook. I knew that they often already had the answer in their heads.

I look Asian therefore I must cook Asian, right?!

When I found a location in Chinatown that was well priced and seem to fit my criteria, I was hesitant to take it. I didn’t want people to think I was cooking only Asian food. When I told a media person about where my restaurant was located, he smiled and said, “great, now you can be with your people” What?!

My Japanese ancestry is only one part of me and doesn’t tell the whole story of me being born in Canada and having so many opportunities and interests in my life. All which influence who I am today and how I cook.

When I opened ZenKitchen restaurant with gourmet vegan food. It was the first of its kind in Ottawa and in Canada. I was pushing past old boundaries and perceptions of what vegan food was.

A friend said to me one day, “I think your thing is inclusion”. I was surprised at first. But the more I thought about it and tried it on for size, it has become one of the words that drive my life and creations.

The thing that struck me most as I started serving customers in my restaurant is that my food while unique and delicious was also inclusive.

Vegan wholefoods are quite pure in that you need to make everything from scratch because you need to know what’s in every ingredient you put in a dish. Therefore, almost everyone can eat it.

In the past, if you were vegetarian/vegan and/or had dietary restrictions and went to a restaurant with friends and family, you were treated differently and sometimes the kitchen would listen to you or not. And while friends and family were eating well at the table, you would often have your unappealing plate of pasta with plain tomato sauce and veg with no protein, and often for a high price tag. I know this still happens today at some restaurants and it isn’t fair.

Where does this deep concern for inclusion and equality come from?

My parents and grandparents of course. And the Japanese who came to Canada and didn’t have this as a given. Unfortunately, many immigrants coming to North America still don’t.

Growing up, I saw my mother experience what I would later know and experience myself first hand as racism. My father’s past of being forced into the internment camps during WWII, even though he was born Canadian and called the “enemy of the people”, was shocking to me when I first found out in my late teens through a high school teacher.

This too has shaped me into who I am today and how I cook.

My wish is that my food helps to change people’s perceptions, stereotypes, and fears of something new that they may have never tried before. And go beyond their comfort zones.

Food is more than food, and more powerful than we realize. Food can be a tool for change.

I never remember my mother and father saying, “I love you.”

But they did say, “have you eaten?” “do you want something to eat?”,” did you have enough to eat?”, “do you need money to get something to eat?”, “take some food home with you to eat later”, and “share some food with your friends.”

What I realize after all these years is that what my parents were really saying is, “I love you and care about you.”

That actions are more important than words.

And food is love.

Also published on Medium.

0 Comments